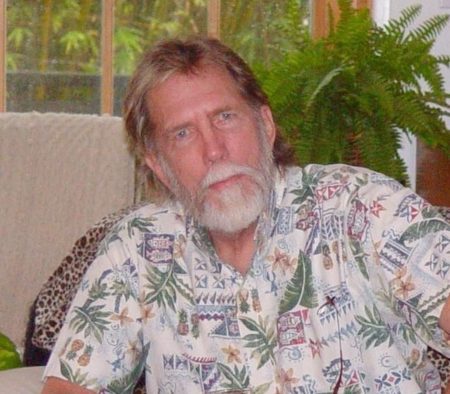

Paul’s Story 1971-72

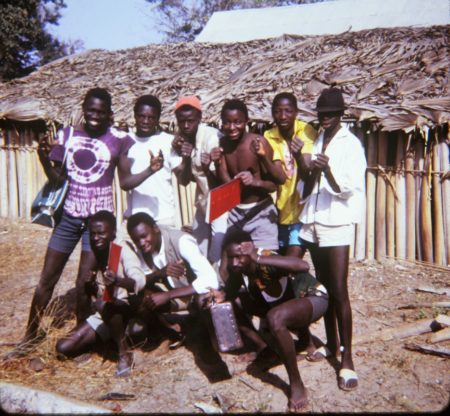

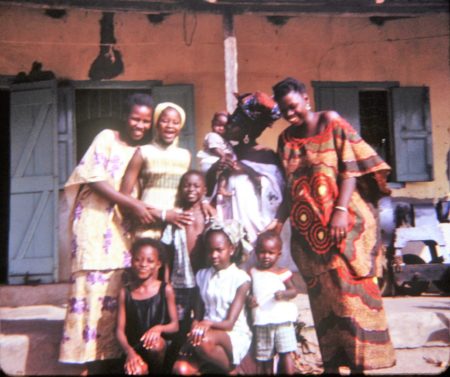

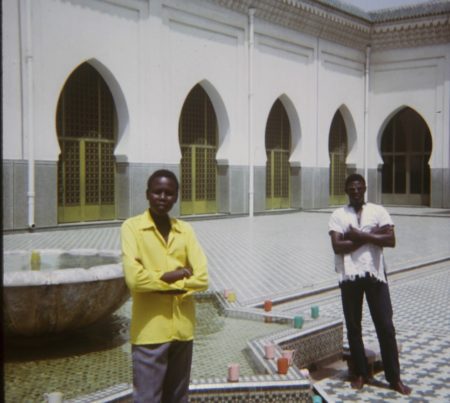

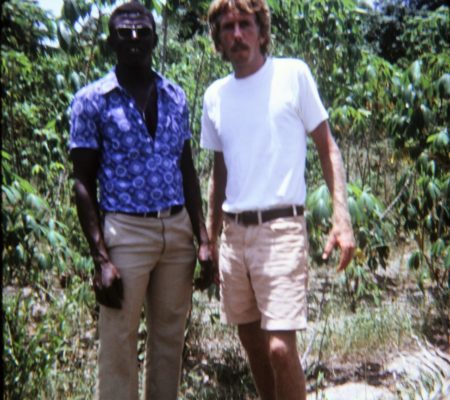

I have been in contact with several people who were PCVs in The Gambia during the early 1970’s. This first installment was written by Paul Stefanson. It is very enlightening to learn about his experiences in the early days of PCTG. Enjoy his photos and story.

This is a true story about experiences that changed my life. After Graduate School, there weren’t many jobs available; I had been thinking about teaching, and one morning I got a call from the Peace Corps in spring 1971, telling me they were looking for Math teachers in The Gambia, West Africa. I told the person I wanted to go!

Getting settled in Gunjur, The Gambia. Many changes occurred while I was in Africa, where I had three tropical diseases that I almost died from, and another deliberate attempt to kill me. Those experiences certainly had a lot to do with what changed my life, but there were other reasons also.

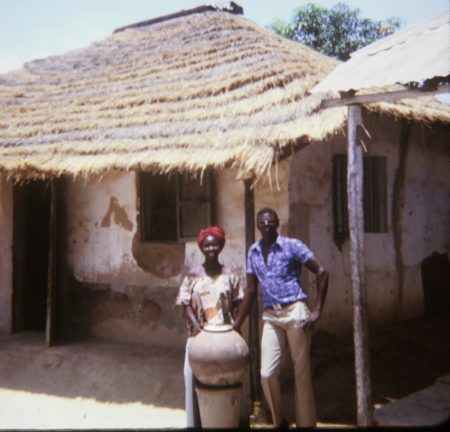

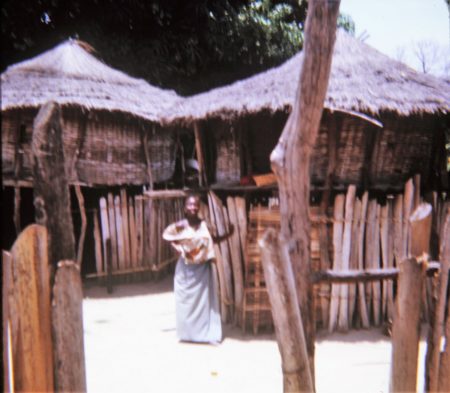

I was placed in a remote village by the name of Gunjur, about 2 miles from the ocean where about 800 people lived. Only the Principal, the teachers, and a few students spoke English, and it took me between three and four months to become fluent in Mandinka, pretty good in Arabic, and some basic sentences in Wolof, Jola and Serahuli.

All the Peace Corps Volunteers were paired off together and sent to teach at schools from the coastal town of Banjul, the capital of The Gambia, up to the easternmost end of the country, 200 miles up the Gambia River to Basse. I was placed alone, 35 miles south of Banjul at the southwestern corner of the Gambia in a remote village called Gunjur, to teach Science in a Middle School.

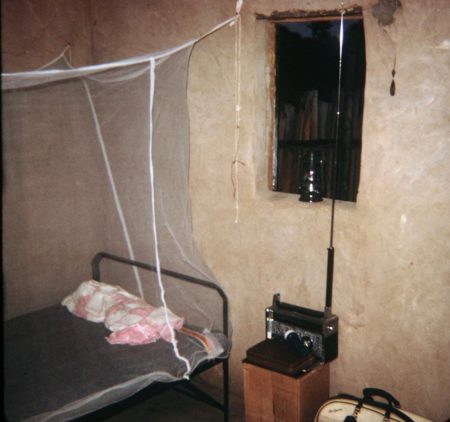

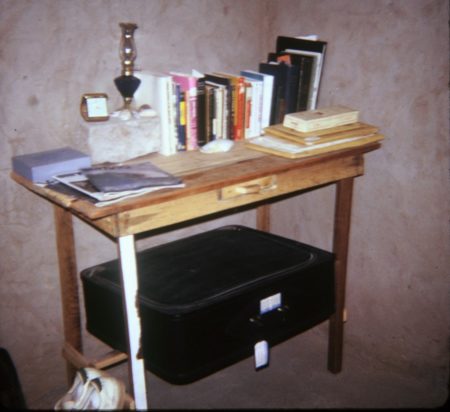

I ate the food provided by a family who lived nearby and drank water from a deep well. This was on a two-acre farm where I lived in a one room mud walled house covered by a corrugated tin roof. There was a library at the Peace Corps Office in the Capital where I could check out as many books as I wanted. I discovered when there was no moon, the light from our Milky Way galaxy was bright enough to read a book, so I would sit outside and read way into the night. If it was raining or otherwise too dark, I would read using a candle on my window sill. Before Africa I had no interest in reading, but once in Africa, I read more than eight hundred books, far more than I had ever read in my life!

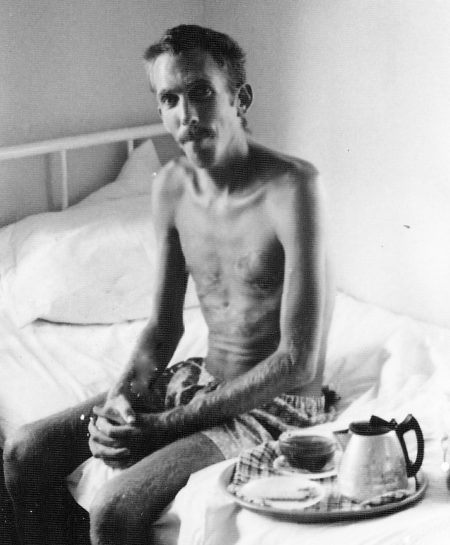

Less than two months after school started I started to feel weak, and I got weaker, until I couldn’t get out of bed. I don’t remember how much time went by until I heard loud knocking on the door; fortunately, someone took the door off and I was taken to the hospital. I was diagnosed with amoebic dysentery. I was in the hospital for almost two weeks, until I was strong enough to go back to Gunjur to teach Science. I thought I was going to teach Math, but they already had a Math teacher.

In the middle of December, I begin to feel weaker and weaker, and was found lying on the ground, covered with flies, half way to the ocean by some nomadic cow herdsmen. They carried me back to the road where a taxi took me to the hospital. I was diagnosed with Hepatitis. The Doctor told me if I hadn’t made it to the hospital that day, I may not have survived! It took me until the first week in January 1972 to recover before I was able go back to Gunjur and teach. I had lost 55 pounds, and now weighed 115.

In April—10 months after I arrived in Gunjur—I started having chills followed by fever, back and forth, in the afternoon, until a terrible headache started that eventually became unbearable! Finally, a few hours after midnight, the headache went away and I would fall asleep. The next day it started all over again in the middle of the afternoon! I thought “Oh no, not again!” On the third day, around 1:00pm, just before it started again, the Country Director and his wife came to visit me; I told them what was happening, and they immediately told me to get in their car and drove me to the hospital. They said I had Malaria and I could die if they didn’t get me there quickly! The Director told me another volunteer in Liberia had died from Malaria. I was in the hospital for a week, then stayed with another volunteer for 2 more weeks before I could go back and teach again.

One weekend, I was walking along this road about a mile when I looked up ahead and saw this 5-foot-tall Baboon 25 yards in front of me standing in the middle of the road with his arms crossed over his chest, staring at me! “Now what do I do?” I stopped and looked at him for a little while, then casually turned around and walked back slowly—at the same speed as I came—hoping he would think of something else to do rather than come after me!

Nevertheless, having survived three near-death experiences (plus the one 10 years before) had a profound effect on me. Why am I still alive? There must be a reason.

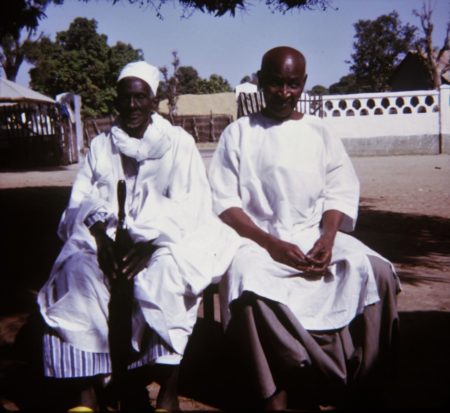

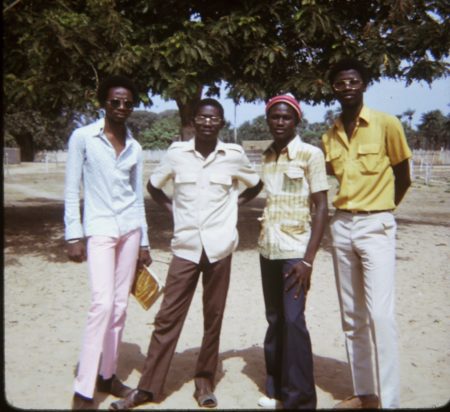

People who have money and possessions have worries. People in The Gambia had nothing. When they woke up, their prime objective was to find something to eat (they knew where to find it), but they were so happy! They loved my sense of humor, and returned it! Once I learned to speak their language—with their help—wherever I went people greeted me, asked me questions and offered me food, treating me like I was part of their family! A gift like that lasts forever. Many of us became good friends, and one of them called Abu became my best friend, and eventually named his son after me!

In class one day, I was shocked when one of the students stood up at his desk and said in English (pointing to the boy next to him): “Mr. Paul, this man blew foul air!” All the boys started laughing, and I was laughing so hard I almost peed in my pants!

I begin to realize that these are the things that make me happy. How wonderful to be happy just like these people are! Maybe I should think about ways to make other people happy when I got back to America. Could this be the reason I’m still alive?

About halfway through the summer break something so terrible happened I thought for sure I was going to be killed! Muslims live and have official status in West and North African countries including Senegal and The Gambia. We had been told during in-country training that almost all Muslims in this area have a negative view of Americans, so we must always respect their religion and customs. I learned Arabic greetings—while learning Mandinka, the language of the Gunjur, where I had been placed—and as many Arabic phrases as soon as I could.

Around the middle of summer, I was walking on a path away from the village. Suddenly, several Muslim people—some I recognized as having given me angry looks whenever we passed each other in the village—came out from the jungle, encircled me and put a black hood over my head! I was led off the path somewhere and put down on the ground, then felt a knife against my throat! I immediately thought “They’re going to kill me! Why? Well, the Quran says “Kill non-Muslims to guarantee receiving 72 virgins in heaven (Quran 9:111)! But I’ve lived through so many things that have almost killed me before, why does it have to end now?

After what seemed like 10 minutes, the person holding the knife took it away. I was thinking “Does this mean they’re not going to kill me?” I heard him get up, walk so far away, and I couldn’t hear what they were saying. A short time later I heard someone walking back to me, taking the hood off and telling me to stand up. That’s when I saw Abu far away with the others; he must have joined them later. The person asked me in English “Why you like us?” I thought about the course I’d taken in college titled “World Religions” taught by professors and other people knowledgeable about various religions throughout the world, so I answered him in Arabic: “Allah-Kalingo-Alai-Undah.” (One God has made us.). He just stared at me, then became calm. I stood there a moment and said “As-Salam-u-Alaikum.” (Peace be upon you) to which he replied “Wa-Alaikum-Assalam wa Rahmatullah.” (May the Peace, Mercy, and Blessings of Allah be upon you).

Abu must have recognized my clothes and shoes I was wearing, and had told the others something like this about me “From the time he came to our village, has always treated us with respect to our religious beliefs and customs, and everyone in the Gambia knows this is the kind of person he is, and he is the only white person who has ever learned Arabic and treated us like this!”

After they walked away, I just sat there and thought about what had almost happened to me—I don’t remember how much time went by—then found my way back to the village.

Goat Express to the Capital. The next day, on Saturday morning, I walked over to the Taxi, a Peugeot 404 Station Wagon, to get a ride to Banjul, 35 miles north. Inside were the driver and 2 passengers, in the back seat were 2 passengers (and a seat for me), and the very back was a cage with 6 chickens and 2 bleating goats tied to the back of the middle seat where I would sit! On the way, we were having fun talking with each other. The driver started asking me questions and I was answering them; when he asked me “Muso Lay? (Where is your wife?) I answered “Mang Muso Soto.” (I don’t have a wife) He asked “Muna-Tina Mang Muso Soto?” (Why don’t you have a wife?” I answered him humorously “Mang Foto Soto! (Because I don’t have a Dick!”) The driver and the passengers immediately burst out laughing! At that very moment, while everyone was still laughing, the most wonderful feeling I’d ever had in my life, a feeling of immense happiness overwhelmed me in such a way that I thought of myself as the hood ornament on the front of this taxi, my back arched, my arms spread outward towards the sky, screaming to the universe: “This is my purpose in life: to help people be happy, and to say things to make them laugh!”

When the taxi stopped at the Capital and everyone got out, everyone talked about how much fun it was and how happy we were during the trip! (I still try to do whatever I can to do kind things for people to make them happy, and to say things to make people laugh! Doing those things makes me happy too!)

Final Days. In August 1972, a few weeks before school started again, Yibu, the Principal of the school, complained to the Peace Corps Country Director, that I had missed too many days of school. I happened to be in the Capital that Saturday, and was asked to attend the meeting. I listened calmly to his allegations (He had never mentioned anything about this to me before). Rather than argue or deny anything, I told him “I sincerely apologize for being away when the students needed me. I’m so sorry.”

After he left, the Director said he wanted to transfer me to a High School in the Capital. I told him I’d think about it. On the way to Gunjur, I made my decision. That night I wrote a short letter of resignation citing “Not assigned to teach in subject of specialization.” (My degree was in Mathematics, not Science).

During the next few weeks, I visited all the compounds in Gunjur where my friends and families lived, thanking them for their hospitality and friendship, telling them how happy I was every day I had lived there! Three girls from the village came over to visit me one afternoon, and brought me a little basket they had made, filled with those delicious Mangoes. Two of them came by the next morning, and I asked,“Where’s Senabu?” Joko told me in a casual manner “Oh, she died last night.” I felt terrible, because I had known them from the time I first came. When I said to them I was going home, they hugged me so long I started to cry.

The following morning, there were more than 100 villagers lined up along the road where I lived, waiting for me to come out for the last time, to get in a taxi with my best friend Abu. They were yelling in Arabic “Baraka!” (Bless you!), over and over, as the taxi pulled out onto the road, away from Gunjur, and all my precious friends.

Saying Goodbye. On the way to the airport, I told him how much I had learned from the people in Gunjur, that I had learned so much more than I could ever have possibly taught! I told him how my living in Gunjur had made me happier than I had ever been in my life. As we got out of the taxi and walked towards the plane, I couldn’t stop the tears as I thanked him for saving my life. He said: “Let’s shake with our left hands.” (Muslims always do everything with their right hand, because they use their left hand to clean up after ‘relieving themselves’). I was overwhelmed with this deeply meaningful show of respect to me. I saw tears in his eyes as he turned and walked away. With tears streaming down my face, I watched him until he was out of sight, then turned and climbed up the stairway into the plane, knowing my life had been changed forever.

I appreciate Paul sending me his story and photos to share. I feel it is important to acknowledge PCV contributions to development in West Africa during the early years. Several other RPCVs have sent me material, and I will be posting more stories and photos in the future. It is very illuminating to see what has, and what hasn’t changed during the 50+ years PC has been in The Gambia.

2 thoughts on “Paul’s Story 1971-72”

Thank you for this wonderful story, Susan. It is people like you and Paul who are working hard to make the world a better, more tolerant place. Wa-Alaikum-Assalam wa Rahmatullah.

Thank you David!

There’s only one race, the human race. The people in Gunjur and I were a family, and whenever I went upriver, everyone was part of this family too! They invited me into their homes where we talked and ate together!

Comments are closed.