Dave’s Story 1971-1973

When I told an Oregon friend I was going to be a PCV in The Gambia, she said her brother had been a PCV there. I reached out to Dave Dupras to ask if he could connect me with other RPCVs from the early 1970s, and the two previous posts about Paul & John, resulted from Dave’s introductions. Dave had his camera stolen while in service (see story below about that experience), so he doesn’t have many photos to share, but his stories paint a vivid picture of his adventures.

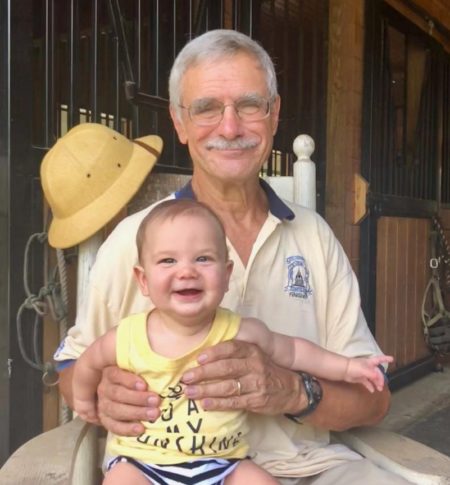

Dave was a PCV in Mbengwi, West Cameroon from October 1968 to April 1971, before transfering to The Gambia. He was a poultry and agricultural extension volunteer, assigned to the Ministry of Agriculture office in Mbengwi, Bamenda, Cameroon. He was also the Agriculture Program Country Director in Mali from September 1976 to October 1977. He currently lives outside of Annapolis, Maryland.

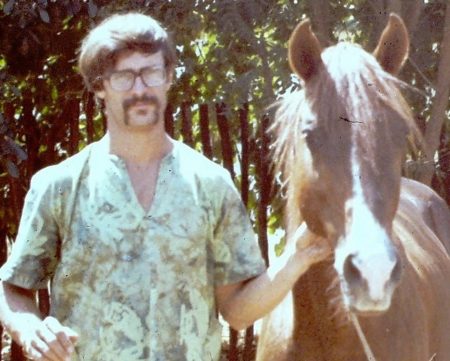

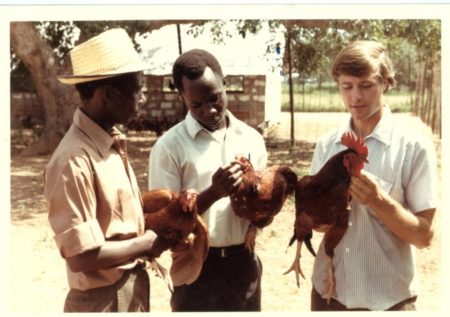

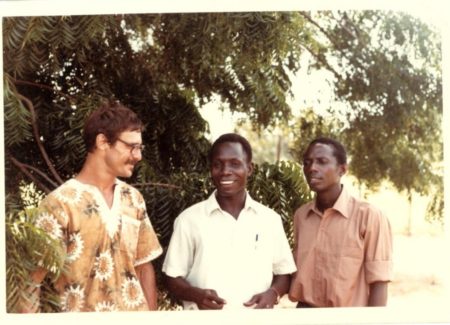

Dave was a PCV in Abuko, the West Coast Region, of The Gambia from 1971-73. He set up a poultry farm on the Veterinary Station there, and traveled around the country distributing baby chicks. He said he tried to learn Mandinka with mixed success. He mastered some Wolof greetings, and has had more occasions to speak Wolof, than Mandinka during his RPCV travels, because the Wolofs were traders, and traveled all over Africa and Europe.

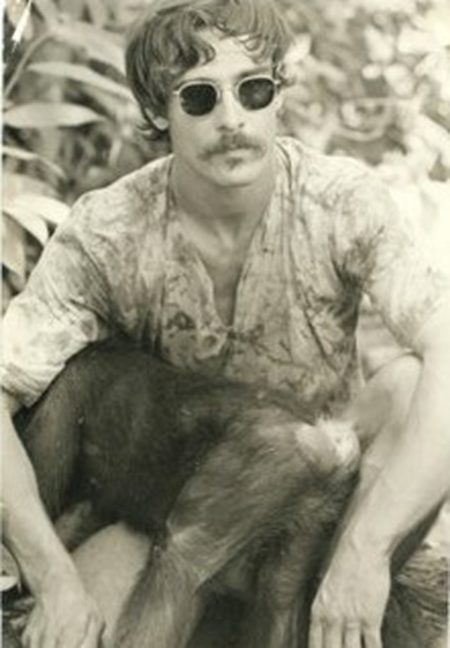

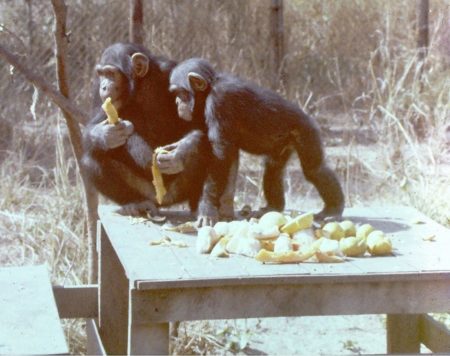

He worked with Eddie Brewer and Stella Brewer Marsden at the Abuko Nature Reserve (ANP), and also did a lot of work with the orphan chimps. He studied primatology at UC Berkeley, and really appreciated the work they did rehabituating the chimps. In 1969 Stella received a few chimpanzees rescued from merchant traders, and established the Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Project (CRP). For the first five years the orphaned chimps were kept at Abuko, but as the animal numbers grew, it became clear that reintroduction into the wild was a better option. In 1979, the project relocated permanently to River Gambia National Park (RGNP), where the chimps were given new homes on the Baboon Islands (I wrote a blog post about my visit to the islands). The CRP is Africa’s longest running chimp rehabilitation project, and is now a sanctuary for over one hundred free roaming chimps.

Dave’s Stories

WILLIE the Chimp

After my normal day as a PCV working in poultry development, based at the Abuko Veterinary Center, I would help out with the orphan animals at the nearby Abuko Nature Reserve, established and managed by Eddie Brewer and his daughter Stella. It’s main source of revenue was as a tourist attraction. The most popular of the reserve’s citizens were the orphan juvenile chimpanzees. They were mainly rescued from local hunters, who had killed their parents for food and were going to sell the babies to collectors. Willie was the most renown of the young chimps.

Willie’s acclaim was due mainly to his curiosity and inventiveness. Had he been a human, Willie would have been an engineer. He was the only chimp in the group of about ten juveniles who could screw and unscrew their milk bottles, we brought to them daily. Even as a two-year-old, he realized that many mysteries in life could be resolved by turning man made things in different directions.

The first application of his engineering skills, was when a German tourist with a Hasselblad camera mounted on a tripod came into the chimp enclosure to take some photos. Willie quietly watched as the man set up his equipment, and watched again whenever he moved it around. After a half hour, we all forgot about the quiet chimp, and focused on the antics of the others as they ate their lunch of fruit. The tourist was concentrating on focusing his Hasselblad, and didn’t notice that Willie had approached the tripod, and had begun carefully unscrewing one of the legs. It was comical. The man kept leaning forward, as the tripod slowly collapsed, until he caught himself and his camera just before they both hit the ground.

Willie grabbed the loose tripod leg and began scampering about, chuckling to himself. A mischievous streak bubbled up in his laughter just as he was climbing a palm tree, and he began playing tug of war with the tourist for the possession of the camera. In the end, we got the camera and tripod back, with no worse for the experience, not that Willie didn’t try.

One of the habits with chimp life, is their natural tendency to groom each other. While normally this is an exceptionally healthy habit, it can cause problems. Once Willie was gored by an antelope he was teasing, and received a cut above his eye, which required stitches. Our local British Veterinarian, Dr. Graham, was able to stitch up the cut, but advised us not to put Willie back in with the other chimps, as they would pull the sutures out. So what do we do? Where do we keep Willie?

We decided to let him stay in the house I shared with a British volunteer on the Abuko compound. We put Willie in the living room after having taken the breakable things out of it. It had a painted concrete floor, which made cleaning up his bowel movements easier, because chimps have poor hygiene when compared to cats and dogs. Willie had never slept under a roof, much less spent anytime in a house.

We kept Willie inside for only two days, as he began to figure out how to escape. Our living room had three doors, a wooden one that went to Willie’s sleeping room, and two metal and glass doors which went outside off either side of the living room. All three doors had lever handles, which opened by pulling them down. Willie’s natural curiosity was whetted. After observing us entering and leaving the room, by opening and closing the doors, Willie tried it. He initially couldn’t get it open, because knowing his abilities, we concealed our handle manipulation with out bodies. Unfortunately, Willie deduced our actions anyway, and after a few experiments was able to turn the handle, push open the door and scamper off into the yard, chuckling his delight. We had to then catch him, and started locking the doors. Although, sometimes we got lazy, and left the key in the locked door, which was sufficient for Willie to learn how to turn the key, then turn the handle and push open the door. So, we had to keep the keys out of the locks. We put them up on a shelf, about six feet off the floor, inside a seashell. Finally, we had to put him back with the other chimps, when he began climbing the shelf to get the key, and then shoving it into the lock, turning the handle, and opening the door. He had to do this under pressure, as we were usually near him when he was in the living room, and we were moving towards him, by the time he climbed the shelf. He had all the motions down, but couldn’t quite master getting the key into the keyhole with any efficiency. He would be turning the key with one hand, and pull the handle down with the other hand, while looking over his shoulder at us. Given another day, he probably would have learned to pick the lock.

CHARLIE the Duiker Antelope

Another notable character in the orphanage was Charlie, a small duiker antelope. Charlie was an unhappy bachelor, we didn’t have a female duiker in the reserve, and he frequently took out his frustrations on whatever was nearby. Fortunately, Charlie was barely 15 inches high at the shoulder so the most damage he did was to our human shins.

There were areas in the reserve which the chimps couldn’t go as they would be able to climb out. Willie, somehow, had gotten into one of these areas, and I had to get him back to where he belonged. Willie knew he was in the forbidden zone, and wouldn’t come to me, no matter how beguiling I coaxed him. So, I had to be more cunning. I pretended not to want him, by looking away, and finally diving at him and grabbing his leg. Willie’s screeches brought Charlie to our little struggle. I was off balance on my stomach and knees, while Willie was biting my hand and backing away further stretching me out in the dirt on my stomach. This was too tempting for Charlie, and before I even knew he was around, he ran full speed into my rib cage. Bruised and sore, I refused to let go of Willie’s leg, and Charlie refused to let go of the opportunity of a “tall one” brought down to his range. This ridiculous scenario continued for an eternity, it seemed. Willie kept backing up, and Charlie kept charging and butting me, bruising my left shoulder and rib cage, when I was stretched out. Finally, I was able to get a good grab of Willie, picked him up, and kicked Charlie away from my legs. It was not a good day, but it was a memorable one.

FOTO – A Mandinka Language Lesson

After a year in The Gambia, I was becoming more confident with my mastery of the prevalent local language, Mandinka, but still had trouble with some of the tonal aspects. There were four different tones in most words, each of which could change a word’s meaning.

I went to the local market to meet a group of farmers for my extension work. As I was hungry, I thought I would order a bowl of hot porridge for breakfast before my meeting. The Mandinka word for porridge was foto, with the accent on the first syllable. Confidently, I told the market lady that I would like to buy and eat a bowl of porridge. Her eyes opened wide, and she asked me to repeat my order. I figured she wasn’t used to a white man speaking her language, and repeated my phrase. By this time a couple other market ladies had come by and had began chuckling. One asked me to say it again. I proudly did so with more feeling, and one lady slipped to the ground laughing convulsively. I had an inkling that I screwed up.

Sheepishly, I walked over to a man and asked him what I’d said. He asked me to repeat what I had said, and then chuckling, he told me that I had used the wrong tone. He said I had ordered a bowl of penises to eat. The Mandinka word for penis and porridge was the same, except for the tone.

THEFT PREVENTION

As a poultry extension agent in the Peace Corps, I had a Land Rover, with a primitive art picture of a Rhode Island Red hen on the door. Everyone knew my car and my whereabouts. For the most, it didn’t matter, except for the nefarious set. When the chicken car was gone, it was an open invitation to pay a visit to my poorly locked home, and choose which of my possessions to steal.

As a PCV, I was making less than $100 per month, and my needs and possessions were basic. Besides my clothes, I had two luxuries – my 35mm camera and a portable shortwave radio. The radio was the first to go. On the second trip my camera was taken. On subsequent visits, the thief took various items of my clothing. By the seventh visit, clean clothes were taken, and dirty ones (taken earlier) were left. There was no way to secure my premises, short of putting bars on the windows. The various attempts I had at trying to trap the thieves had been in vain, and the local police efforts were half-hearted and incompetent. I was a rich Tubob. After seven times, I had had enough, and sought traditional solutions.

After conferring with my Gambian counterparts, I was told about El Hadj Alkali Mamadou Moussa N’diaye, an Alkali or Witch doctor and Muslim Imam, with mystical powers. He lived up country in Senegal. I decided to visit him on my next trip up the River Gambia.

In preparation for my visit, I was advised to bring traditional gifts for the El Hadj, which included kola nuts, salt, candles and some Senegalese coins, but not paper money. Traveling with Gambian colleagues and my gifts, we crossed into Senegal, taking dirt black-market peanut truck routes. Gambian peanut merchants paid cash for peanuts, while Senegalese merchants paid in chits to be redeemed months later. Therefore there was a thriving illegal market for Senegalese peanuts in The Gambia. As it was the dry season, the countryside was brown and dusty with very little vegetation.

We came to a grove of huge baobab trees, and my friends told me we had arrived at the Alkali’s compound. There were two houses with expensive corrugated metal roofs near the trees, and three vehicles beside the houses – one pickup truck and two Mercedes Benz sedans. I was told that rich men from Dakar came to see the Alkali, so they could become more powerful. We had to wait an hour for the wise man to see us. He was old, with withered wrinkled skin, dressed traditionally in a flowing light blue bobo and white cap. He was sitting in a lounge chair,in a large room with some of his people standing beside him.

My group and I approached. As instructed, I laid the salt and kola nuts at his feet, and gave him about $5 in West African francs, wrapped up in paper. As my Wolof was not fluent, I spoke to him in English, which was translated into Wolof by my colleagues. I told him that I was a “chicken doctor” and recounted the seven thefts of my property. He nodded he understood, and spoke to me. He said he could help me, but that he could not promise that my possessions would be returned. He said he could give my soul peace, and that he would ask Allah to punish the bad people, who stole things from me. He asked how I wanted them punished and gave me three choices – make them blind, drive them crazy, or kill them. I wasn’t prepared for the enormity of my decision, and after some hesitation replied that driving them crazy would be satisfactory, as blinding someone, or killing them seemed too harsh for petty theft. He again nodded his understanding and instructed me to come outside with him.

We walked to the grove of baobab trees, which were growing in a circle. The trees were enormous and must have been hundreds of years old. There were nine of them. The Alkali instructed me to walk around the trees clockwise three times, holding my hands shoulder height, palm upward repeating Allah Akbar, God is Great. I walked alone in the dust around the circle of ancient trees. When I finished my third circuit, I stopped in front of the Alkali, who then spat in each of my hands. Startled, I asked my friend what to do, and he said I should put my hands together without wiping anything off. I did so. With face skyward, and his palms up at shoulder height, the Alkali said some prayers for me, smiled, and said the thefts would stop. He then shook my hand, and I thanked him. He turned away and returned to his house, while my group got back into the Land Rover and returned to The Gambia.

That was the last time I ever had anything stolen from me in The Gambia. I looked to see if anyone was driven crazy, but never noticed anyone, or found my lost possessions. My soul, however, was at peace.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

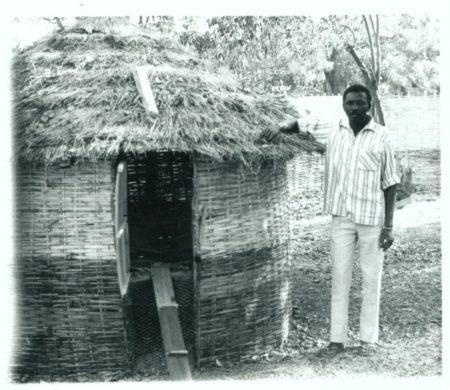

After World War II, Great Britain decided to exploit the natural resources and warm weather of its closest African colony, The Gambia, to develop a large egg producing poultry experiment. The colonial masters built a number of large European designed poultry houses in Yundum, for thousands of egg laying Leghorn hens. About two miles away, Great Britain also installed a 960 electric egg incubator for the fertilized eggs from the breeding flock, to keep the operation sustainable. The weak links in the chain was the feed and transportation costs. Most of the feed was shipped in from Europe, and also the high cost for the refrigerated boat trip back to Great Britain with the eggs, was expensive. There were plans to grow corn in The Gambia, but the production was not successful for a variety of reasons. The cost effectiveness of the poultry experiment was not sustainable, so after less than a decade the whole operation was shut down. The poultry houses were converted into warehouses, garages and offices for the Ministry of Agriculture. The incubator and surrounding buildings, located in Abuko, were given to the Department of Veterinary Medicine, which used them for storage facilities.

As a PCV I served in small farmer poultry extension work for over two years in Cameroon. USAID had developed a poultry farm with an incubator, and distributed Rhode Island Red day old chicks for sale throughout West Cameroon. When my tour was up I sought other PC opportunities in Africa, and was sent to The Gambia to continue my work.

POULTRY DEVELOPMENT in THE GAMBIA

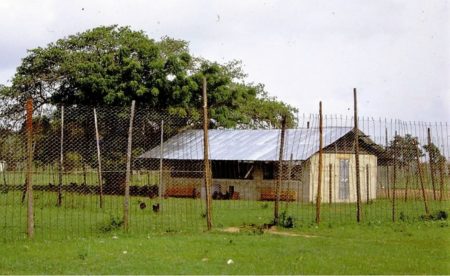

I had worked with poultry extension PCV in Cameroon from 1968-71, and then transferred to The Gambia to start up the country’s poultry center. I designed and helped build five large deep litter poultry houses. Five hundred Rhode Island Red breeding chickens, were brought in from the USA as day old chicks. With help from a UN electrical engineer, we rewired and salvaged an old British incubator, so the center was able to hatch up to nine hundred eggs at a time. We then sold the day old Rhode Island Red chicks to local farmers, as a way to improve nutrition and generate income.

Initially my work was providing extension advice to small scale poultry farmers around the capital city of Banjul, which was called Bathurst back then. Most of the farmers were middle class government workers, who had flocks of about twenty birds. One of my “clients” was Sir Dawda Jawara, the country’s first president, and a Great Britain educated veterinarian.

I was initially based in the Department of Veterinary housing in Abuko, where I found a non- functioning incubator in a small room in a warehouse. I also discovered the incubator operational manual, wiring diagram, and tried to get the machine functioning. No luck! By chance I met an electrical engineer from Trinidad working for UNESCO in The Gambia, and asked him for help. He inspected the old incubator, and discovered some shorts in the electrical system, and repaired them. He also replaced a few parts, and got the machine working again. We were ready for business, and all we needed were fertilized eggs.

As the Veterinary Department had insufficient funds to buy the improved poultry chicks needed to start up a hatchery, the PC director suggested I contact the US Consulate in Bathurst for a $500 grant from the Ambassador’s self-help fund. I did some research, and found that it would be cheaper to fly in breeding stock of day old chicks from the USA, than from Europe. I wrote out the grant request, got it approved, and bought 500 day old grandparent Rhode Island Red chicks. Grandparent poultry can be bred for two generations without diluting or losing desired characteristics. I selected the Rhode Island Red breed since they were a hearty dual purpose bird, for both eggs and meat, and had done well in Cameroon. Rhode Island Red chickens were not as productive as Leghorns, but were calm birds and easier to raise.

About a month later, I received a telegram on the same day the chicks arrived at the airport in Senegal, a six hour drive away. I had to drop everything, rush up to the international airport in Dakar, and clear customs with my minimal French. I was concerned that the chicks would die, since they were hatched 48 hours earlies in the USA, before they were put on the airplane. I drove through the night eating kola nuts to stay awake, and finally returned to The Gambia in time to catch the first ferry boat across the river. I arrived in Abuko, unloaded the chicks, and discovered I had only lost five birds. I put them into the hatchery I had made inside a shed, using a cardboard carton circle with a couple of hurricane lanterns for warmth and light, gave them water and some chick feed. The first night was critical, so I slept near them, continually checking them over to insure they were warm enough, and had sufficient water. All was well the next day.

While the chicks were growing in the hatchery at the Veterinary Department, I had begun constructing a poultry house that I had designed, which was appropriate for the climate. The end walls were facing the directions of the prevailing winds, and the sides were open but covered in small mesh wire to keep wild birds out, but to allow for cross ventilation. The overhanging roof protected the inside from direct sunlight and rain. The floor had about two inches of peanut shell litter. The nest boxes were built using local wood. The hens could enter from inside the house, and staff could collect the eggs from the outside, by unlatching and lifting up the lids. An eight foot high fence surrounded the poultry yard and house, to keep out predators and thieves. At about the same time we planted a half acre of native sweet potatoes for green feed, as a diet supplement. We bought the drinkers and feeders from a store in Dakar. Later on, we developed a low cost ration using local feedstuff, adding concentrate purchased in Dakar. We put all the birds on a strict vaccination schedule, as fowl diseases were common in The Gambia, which is a major flight path for wild birds to and from Europe and Africa.

The Rhode Island Red birds were not sexed when purchased, so we had about 50% cockerels. When they were ten weeks old, it was obvious which were male and female. We then separated them by sex, and sold the cockerels off for breeding purposes to small poultry farmers. We kept fifty cockerels for breeding purposes for the approximately 250 pullets. We used a ratio of one cock per ten hens, to fertilize the eggs, and rotated the cocks in as a group every three months. I learned the hard way not to rotate individuals or small groups of cocks, as the ones already in the yard would attack them.

After about five months the hens began laying eggs, and after eight months we began trying to hatch the fertile eggs. The first batches had mixed success, but after a month we were hatching over 60% of the eggs, and within two months we had over a 75% hatch rate. We sold the surplus eggs to hotels, the unsexed chicks to local poultry farmers, who had previously bought their chicks from Europe. We expanded beyond Bathurst, and began taking orders and delivering day old chicks up county to schools. We had a cadre of Veterinary Department Agents providing extension advice to the poultry farms.

After a year of production the demand for chicks increased as did egg consumption among the local population. We began using the best of the day old chicks as a parent breeding flock, building another poultry house for 250 more hens and cocks. We then used some of the profits from egg, cockerel and chick sales to buy 200 more grandparent Rhode Island Red day old chicks from the USA, and built two more poultry houses for the new flocks. As the poultry industry grew we received requests for broilers. Initially some of the excess cockerels were sold as roasters. It took five months to reach the desired weight, and it was a waste of their genes for breeding with the local hens. Therefore, we began importing day old broilers and turkeys from Europe for the Veterinary Department and private farmers. After about three months, we created the first halal poultry slaughter operation in The Gambia, and the Veterinary Department had a new revenue source. Due to demand, there were plans to buy either broiler parent stock, or fertilized eggs for incubation, but that was still in the planning stage when I left.

In 1973 I had been in The Gambia for more than two years, and my time as a PCV was over; I handed over the poultry operation to my PCV replacement Dale Davis and the talented crew of Gambians who had become very expert in their mastery of intensive poultry management.

ANOTHER STORY – THE GAMBIAN GOLDEN GOOSE

Thanks to the Swedish entrepreneur, Britt Wadner, the first batch of blue collar Swedish tourists flew into The Gambia in the early 1970s to escape the cold Viking winter. One of the early tourists who flew in was a Swedish farmer, who was also a good mechanic.

After a few days of getting sunburned on the beach, Sven decided to take a walk along the beach front. During his walk he noticed a couple of abandoned British built tractor carcasses. He asked one of the local men about the tractors, and was told that they used to run, but had broke down, and since there were no spare parts, it was just left there. It had sat for some years. Intrigued, Sven borrowed some tools and took one of the tractors apart until he found what was broken. He did the same to the other tractor. After a couple days, he found a few more tractors, and also diagnosed their failures. He realized that many of them were easily repairable, and carburetor-related problems. He noted the makes and model numbers of the dead tractors, before heading back to Sweden at the end of his vacation.

A few months later Sven returned to The Gambia, but not as a tourist. He had brought along his own tools, some money and a good stock of spare tractor parts. He went back to the farmers he had talked to, and negotiated to buy a few broken down tractors, that were sitting on their land. He rented a truck, and hauled them back to a garage he had rented. He repaired the ones he could fix most easily, sometimes cannibalizing parts.

As this was just before peanut planting season, he offered to plow farmers’ fields so they could more easily plant peanuts, rather than cultivate by hand or with animal traction. He initially charged a nominal fee but later increased it to a more profitable rate. He trained a number of promising Gambian men in the art of cultivating the soil using tractors and established a fleet of tractors for hire. He taught them how to plow at night when it was cooler using the headlights. Nobody had ever plowed at night in the Gambia before. By the second year business was booming, and Sven was buying more tractors, and importing spare parts to repair them.

By the third year the local politicians had realized what a cash cow the tractor industry had become, and devised ways to part Sven from his tractors, and eventually kicked him out of the country.

By the fourth year the tractor fleet was broken and the machines again sat idle in the fields where they broke down and farmers were once again cultivating their fields by hand or with donkeys.

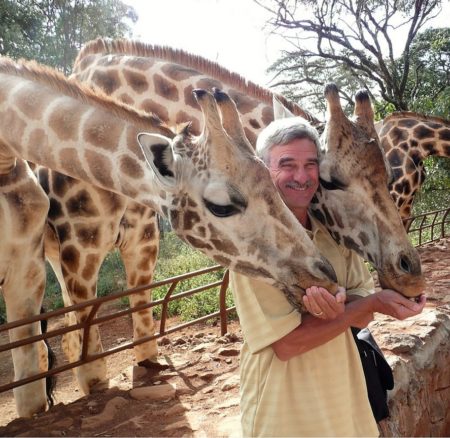

Comment about the above photo: When I left The Gambia, I had some interesting traveling companions from Mauritania to El Ayun across the Sahara. It was a long night. I sat between these two camels and got lots of fleas. I also was peed on, but at least I was warm for awhile.

EPILOGUE

I left Peace Corps The Gambia during the summer of of 1973, and traveled by land through the Sahara using “public” transportation, along the western coast of Africa through Senegal, Mauritania, Spanish Sahara into Morocco and through Europe before finally reaching home in California six months later. As I had a burning desire to go to graduate school, I entered a local junior college in Oakland to retake all of my science courses, as the sciences had evolved so much during the five years I was in PC, and my old course work would not help me for graduate school classes. After completing these science courses, I was accepted into Cal Poly at San Luis Obispo where 18 months later I obtained a MS in agriculture.

Having been stationary for two years, wanderlust kicked in and I decided to drive up to Alaska through Canada in April, to look for work and found two jobs. A full -time job with the University of Alaska doing laboratory work in soil science and plant-tissue analysis, and a 20+ hour a week job managing the 12,000-hen poultry flock in Wasilla, it was the largest egg production farm in the state, but suffered from bad management. I was able to increase egg production by 400% in two months. After 6 months I got a call from Peace Corps in Washington, DC to become the Agriculture Program Country Director in Mali. With mixed feelings. I left Alaska to return to Africa.

During staff orientation in Washington, DC, my French competency was tested, and was found wanting. Peace Corps sent me to Bamako, Mali under the condition that I take an intensive French training at a TEFL (teaching English as a foreign language) program in Upper Volta a couple months later. I went to Ouagadougou for the two-week program where I met Connie, a RPCV from Cameroon who was teaching TEFL. She followed me to Bamako, and we got married a year later.

I left PC Mali after a year, and took a job with a DC based consulting firm, I spent the rest of my career doing work in international agriculture, and rural development, mainly in Africa but also working in Asia, Eastern Europe, Central America and the Caribbean. Connie gave birth to our son in Tunisia, and to our daughter in Rwanda. We returned to the USA in 1986, but I continued working for international consulting firms until my retirement in 2013.

Since I retired from full time international development, I have done various short term assignments back in Africa, some as a volunteer, some as a paid consultant. I am active as a volunteer for the Maryland Department of Agriculture, and also work with the University of Maryland Cooperative Extension Service as a Master Gardener.

This is the last of my historical posts of PCTG. I want to thank Dave, Paul and John for sharing their stories and photos, and encourage other RPCV to write about their adventures. It is fascinating and inspiring to read about the early days of Peace Corps.

One thought on “Dave’s Story 1971-1973”

These stories are so interesting! Thanks so much for sharing them.

Comments are closed.